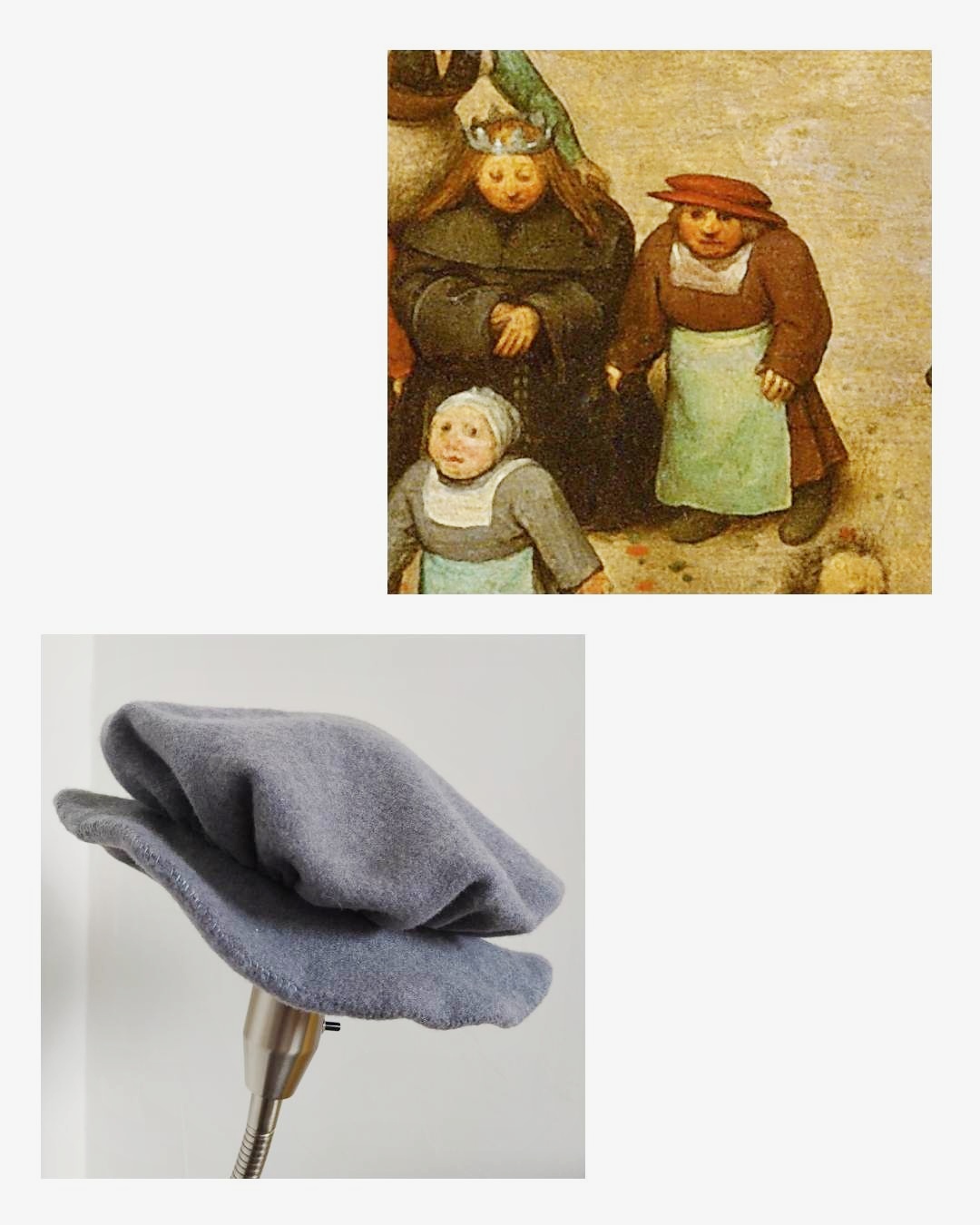

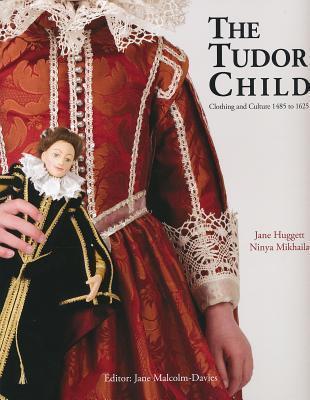

I hesitated for a long time before sewing this bonnet as an accessory to a children's costume from the Thirty Years' War, as it does not fit into the Czech environment at that time. However, since theoretically such an appearance would not have been completely impossible in the Czech lands at that time, and since people tend to turn a blind eye to period accuracy when it comes to small children, I sewed it anyway due to my great fondness for this accessory. It was originally sewn for my son according to a pattern from the publication The Tudor Child: Clothing and Culture 1485 to 1625. As soon as it was made, his younger sibling took a liking to it, and so we soon had a little Tudor girl at events.

What did I want to achieve?

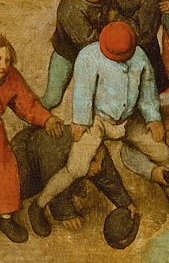

BRUEGEL, Pieter the Elder. Children´s games

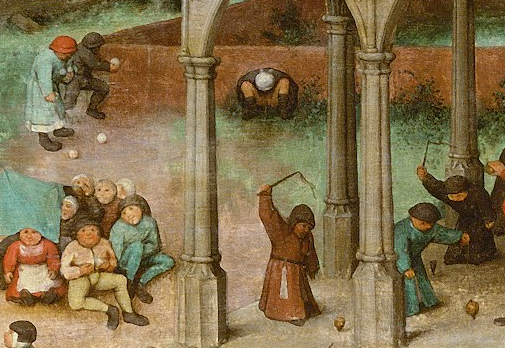

The inspiration comes from my favorite painting, "Children's Games" by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, painted in 1560, which depicts a number of bonnets on children's heads, see a few details below.

Many such bonnets are preserved in museums, where we can also find knitted versions that were more common among the common people. Since I forgot how to knit a long time ago, I chose the sewn version.

A woolen knitted cap from the London Museum, with short pieces of silk ribbon sewn into it. In the 16th century, hats were fulled (washed, beaten, and felted) after knitting to create a strong, warm, waterproof, and durable fabric. The hat dates back to the Tudor era, and just like in Bruegel's painting, we can find various styles among the preserved specimens (depending on the customer's taste and wallet). According to the museum's description, the production of a single cap is the result of the work of highly skilled, professional workers. Bright colors such as blue or red were common, but black and dark brown were also worn. Most caps today are shades of brown due to long-term exposure to damp soil – dye analysis would be necessary to reveal their original color.

For those who would like to knit such a cap, there is also a technical description of the knitting process in the image link. I would like to point out that the knitted version is very stiff due to fulling, without any elasticity or "flexibility," as stated by the museum. To the touch, it is more like fragile felt than soft knitwear.

Another preserved cap, split-brimmed with slashed neckflap. Workers digging foundations for new buildings around London in the early 20th century found many pieces of clothing and textiles buried in the ground. Many of them are caps like these, most of which are in good condition. They were probably lost from the heads of their wearers or discarded when they became unfashionable (around 1570) and thrown into city ditches and cesspools. Unfortunately, as these were not formal archaeological excavations, all details that could help to date the caps more accurately were lost.

MOR, Antonis. Portraits of Sir Thomas Gresham and Anne Fernely

Sir Thomas Gresham (1519–1579) wearing a cap.

HOLBEIN, Hans the Younger. Edward VI as a Child

Another portrait of Prince Edward, also wearing a cap.

LYON, de Corneille. Portrait of a Man

This portrait shows a simple, single-color version of the bonnet. According to museum descriptions, these caps were sometimes also referred to as "apprentice" or "statute" caps. In 1571, a law was passed requiring every man over the age of six, with the exception of men of high rank, to wear a knitted woolen cap made in England on Sundays and holidays.

BRUEGEL, Pieter. Peasant Wedding

We can find lots of bonnets in other Bruegel paintings too. Museums say that some of them were trimmed with ribbons to look like the pricier silk versions. Wealthy Londoners wore headgear influenced by European fashion, and bonnets from Milan, decorated with ostrich feathers and brooches, were particularly fashionable. The painting depicts villagers (detail).

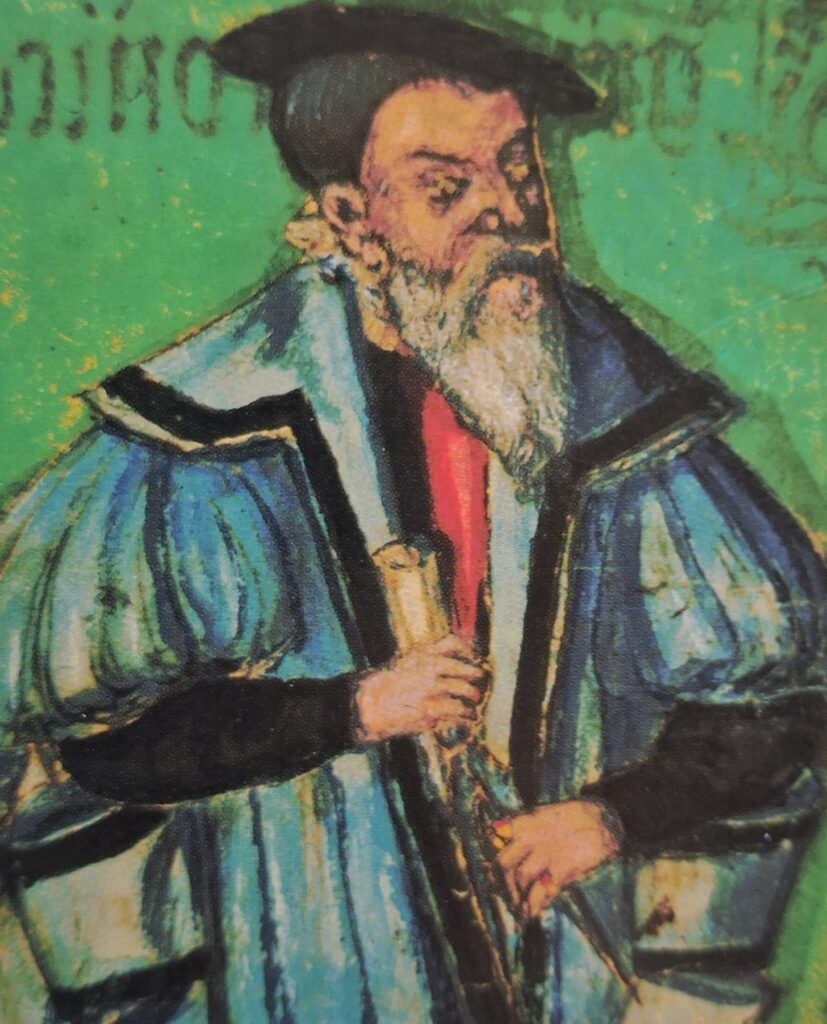

HASELBACH, Pankraz engelhard von. Chebská kronika

One domestic flat cap belonging to Bernhardin Schmidl, mayor of Cheb, photo taken from the publication Clothing in Western Bohemia in the 15th to 17th Centuries by Veronika Pilná (p. 45). In her publication, the author states that the large flat bonnet was a popular head covering for both men and women in the first half of the 16th century. It was worn on a hair net and tilted to one side, decorated with jewels and feathers. It quickly became popular among broad sections of the population, from nobility and townspeople to soldiers and mercenaries. (p. 51). At the end of the 16th century, bonnets were replaced by completely different types of headgear in Bohemia.

HASELBACH, Pankraz engelhard von. Chebská kronika

A photo from an illuminated manuscript is also included in the publication Clothing in Western Bohemia in the 15th to 17th Centuries by Veronika Pilná (p. 251) and depicts an older man—the primate of the city of Cheb—wearing a simple black bonnet set at a slight angle. Veronika Pilná also mentions in her publication knitted bonnets from the 16th century found in London and made using the circular knitting technique with multiple needles. It is not known to what extent this technique was used for bonnets in Bohemia, but it was used here as such (p. 51).

Step by step

The pattern comes from my favorite publication, The Tudor Child: Clothing and Culture 1485 to 1625. It is very simple and can also be used for adults. It is suitable for the period 1485-1580 for all social classes and for the lowest class until 1625. According to Veronika Pilná, this type of bonnet was geographically very widespread - it was worn not only in Western Europe, but also in Central and Southern Europe (Oděv v Západních Čechách 15. až 17. století, str. 51).

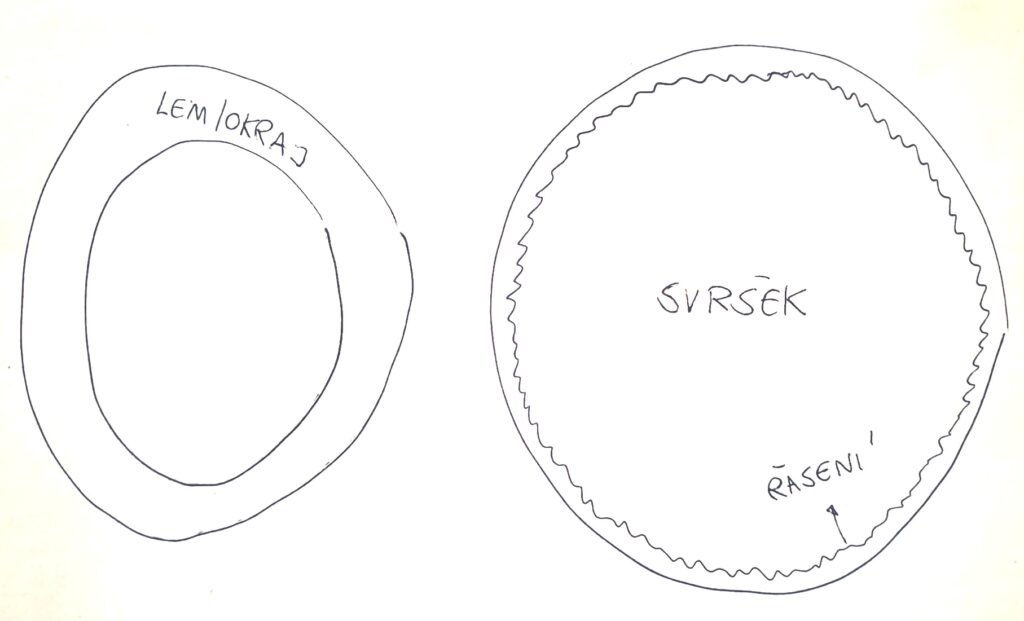

Střih v knize uvádí velikost baretu pro 10leté dítě s obvodem hlavy 56,5 cm. Střih lze přizpůsobit velikosti hlavy nositele jednoduše tak, že se zvětši nebo zmenší obvod vnitřního lemu - okraje baretu, tedy úpravou jeho vnitřního i vnějšího obvodu. Dle publikace se k odpovídající velikosti přidává 6 mm délky navíc.

Pro jednoduchý vlněný baret, jaký jsem tvořila já, je zapotřebí vystřihnout dvě vrstvy spodního okraje. Pro ty, kteří by chtěli trochu lepší verzi baretu, lze do okraje všít drátek, kterým se baret dá při nošení různě tvarovat. Mně taková varianta připadala u dětí zbytečná a proto jsem ušila jednoduchý okraj bez drátku, který funguje velmi dobře.

Oba kruhy - vlněný svršek baretu i lněnou podšívku jsem dala k sobě a tlustou nití nařasila. Obvod nařasení musí odpovídat vnitřnímu obvodu spodního okraje baretu. Já jsem baret nařasila nejdříve tlustou bavlněnou nití pro nastavení odpovídajícího objemu a poté zašila hustším švem, Takto sešité nařasení jsem pak připojila ke spodní části baretu.

Po spojení horní a spodní části baretu je zapotřebí připevnit na nařasené připojení svršku baretu proužek podšívky (jakési zakončení hrubého spojení obou dílů) - já jsem použila len světle šedé barvy. Proužek látky by měl být 2,5 cm široký a měl by být stejně dlouhý jako obvod nařasení/vnitřního lemu spodní části baretu (je třeba jen přidat něco na okraj délky).

What did I use?

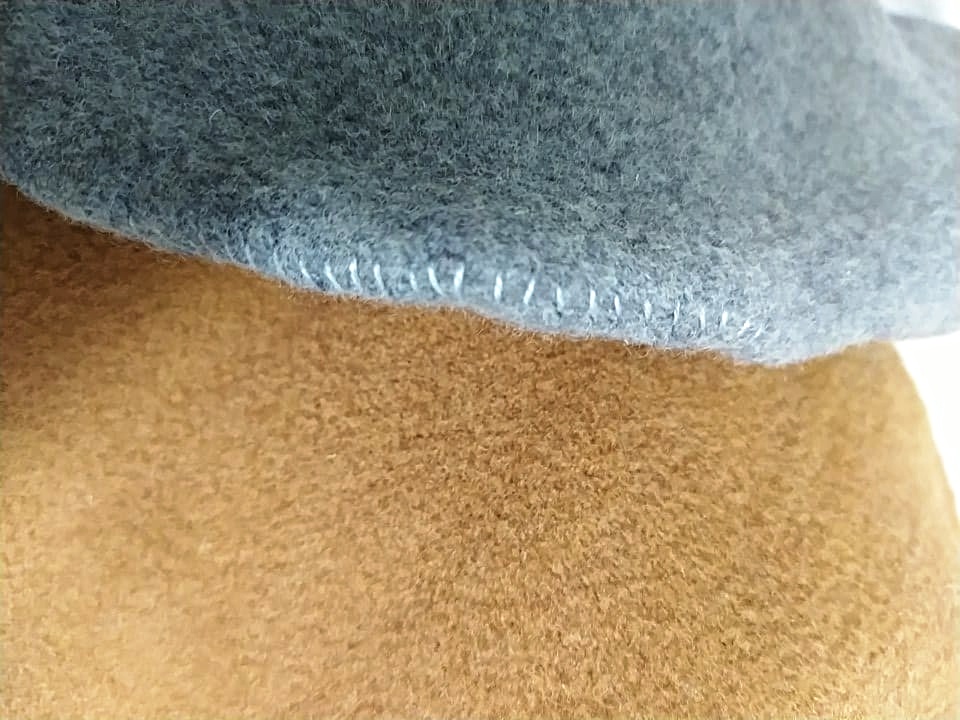

- Teplou, příjemnou vlněnou látku (stačí recyklovat, či použít zbytky)

- Zbytky lnu pro podšívku a lem okraje baretu (opět lze recyklovat či použít zbytky)

- Silnější niť/provázek pro hrubé nařasení okraje/lemu baretu

- Lněnou šedou niť na švy

What will I do differently next time?

- Baret se nám jeví doposud jako perfektní a neměli jsme k němu zatím žádné výhrady, snad jediné, co mi pořád vrtá hlavou je, jak ho ušít rostoucí. Teoreticky mi připadá stejně jednoduché/těžké ušit novou velikost baretu jako zvětšovat baret stávající.

Highlights:

- Je dobré zvolit teplou, hustě tkanou vlnu, aby byl baret co nejteplejší a nejodolnější nepřízni počasí.

- Použití baretu se vyplatilo především při dešti, kdy hlavu opravdu dobře chrání před zmoknutím díky dvojí vrstvě teplé vlny a lněné podšívky. Dá se nosit přes čepec, kdy zahřátí dvojitou pokrývkou hlavy funguje velmi dobře při silném větru a chladném počasí, a to především kvůli tomu, že má dítě díky čepci zakryté i uši.